Introduction

Our planet is facing the severe impacts of human-driven climate change in the form of rising sea levels, heatwaves, flooding, landslides, wildfires etc. that have resulted in massive destruction of lives and property. A recent BBC analysis found that about one-third of the days in 2023 saw the global temperature to be 1.5°C higher than the pre-industrial levels, making this year the hottest on record. Global temperatures will continue to rise in the upcoming years if consistent, large-scale efforts are not adopted to reduce environmental degradation. It is crucial to ensure that global temperatures do not exceed 1.5°C of pre-industrial levels and are kept well below 2°C to prevent huge climate catastrophes.

Merely 100 energy companies accounted for 71% of the global carbon emissions since 1988 (Carbon Database Report, 2017). Apart from the energy industry, the fashion industry accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions, food production accounts for 26% and the transport sector accounts for 1/5th of the emissions. These sectors are mainly dominated by corporations and private companies and they play a vital role in reducing GHG emissions and mitigating the climate crisis. Hence, there is a need to ensure that companies adopt sustainable practices at all stages of production and distribution. According to OECD findings on the impact of EU’s climate change policy, it was found that 10% of CO2 emissions can be reduced without affecting the financial performance of companies. Yet, the lack of conscious efforts by the private sector has led to large-scale environmental degradation and pollution.

What is Greenwashing?

Greenwashing is a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in an essay written by him in 1986, where he criticized a resort in Fiji for asking guests to reuse towels as part of their water conservation strategy. He found this measure to be ironic as the resort was showing that it cared about the environment when in reality, it was constructing more bungalows on the island. He concluded that this strategy was used to merely reduce its laundry costs.

Since then, greenwashing has been a term used to refer to the misleading and false claims made by corporations, governments and other organisations about the sustainability of a product, service or business operation. Companies often use this tactic to cover up their poor environmental performance while at the same time improve their public image.

Why does greenwashing take place?

Promoting sustainability and the adoption of green labels help firms generate profits. Consumers tend to have a positive attitude towards brands that are sustainable and undertake fair-trade practices. In a survey conducted by Bain and Company in 2020, it was found that over 60% of consumers in urban India are willing to pay a premium for sustainable products.

Investors are also increasingly assessing companies on their ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) performance. They are more likely to invest in companies with better ESG performance as they are considered to be less risky and are expected to yield better financial results in the long-term. Often when a company or industry’s environmental malpractices become known to the public, pressure mounts on them from stakeholders to take environmental action.

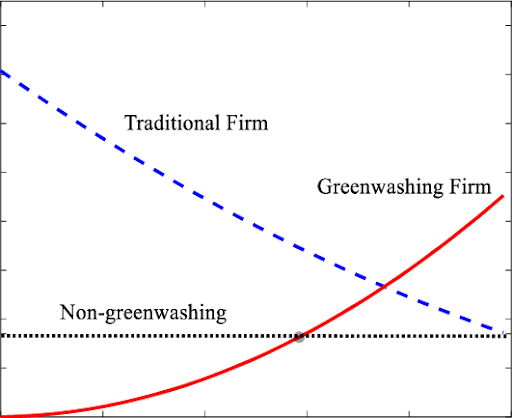

However, corporations aim to promote a green image of itself without having to incur a large amount of operational and financial costs. On sensing a gradual rise in public pressure, such companies resort to quick-fix solutions over long-term efforts to reduce pollution and emissions. They use deceptive tactics in the form of advertising, product design, performative campaigns etc. to evade accountability.

Pervasiveness of Greenwashing

Over the years, there has been a skyrocketing increase in “green” products in the markets. Companies also launch superficial campaigns and CSR initiatives in response to the pressure from stakeholders. Major examples of greenwashing include:

- BP or British Petroleum, a fossil fuel giant, popularised the term “carbon footprint”, and unveiled a carbon footprint calculator in 2004. This tactic allowed the company to shift the pressure of climate action and emission reduction from itself and onto the consumer.

- Coca-Cola claims that its plastic packaging is eco-friendly and recyclable. Coca-Cola spent millions on advertising that its bottles are made of about 25% marine plastic but at the same time remains the world’s biggest plastic polluter.

- H&M, one of the biggest fast fashion brands, came under intense scrutiny for launching the H&M Conscious Collection which claimed to be using less water for production but was using more. The company remains one of the biggest polluters and has been accused of several human rights violations.

Greenwashing can be found across industries. Biodegradable plastic bags, products made of recycled materials, and ‘non-toxic’ cleaning materials are some of the daily-use goods which are not as sustainable as they claim to be. Over time, greenwashing tactics have become more sophisticated and complicated for consumers to identify. Even COP27, the UN climate conference, was accused of greenwashing over its sponsorship deal with top-polluter Coca-Cola.

How to detect spot greenwashing by companies?

Greenwashing can take place in multiple forms which include:

- Vague language: The products are marketed using terms like “green”, “natural”, “planet-friendly”, “organic”, “sustainable” etc. without details on the standards, practices or evidence.

- Deceptive imagery: Using imagery of forests, flowers, water bodies etc. on the packaging to create a deceptive image of how the company is environmentally conscious.

- Hidden trade-off: A company makes insignificant changes or focuses on a few attributes and uses this to knowingly conceal other harmful environmental impacts. Examples include the promotion of electric vehicles without acknowledging the environmental impacts in the process of mining for lithium batteries and the making of the vehicle itself.

- No proof: When companies make baseless claims without producing supporting information or third-party certifications.

- Irrelevant claims: A company can give a truthful but irrelevant or unhelpful claim. Example: Claiming products are CFC-free when chlorofluorocarbons are banned by law in most countries.

- Partnerships, sponsorships and research funding: The company can collaborate with NGOs and other corporations for research and other initiatives to gain a green-label.

- Claims promoting the lesser of two evils: When the product claims to be more environmentally friendly than the others in the category but the whole category is unsustainable. Example: Promotion of natural gas as a clean fuel in comparison to coal, petroleum etc.

- Long-term targets: Many companies have made climate pledges to attain carbon neutrality but have set targets for 2040, 2050 and so on. This shifts the burden on future generations to make changes.

Conclusion

Companies treat climate change as a corporate social responsibility issue rather than an inherent business problem that needs urgent attention. Climate action demands corporations to adopt degrowth, and harm-reduction strategies like transparency, stricter environmental regulations, third-party auditing etc. Corporations will also have to make durable, biodegradable products and remodel their responsibilities surrounding the after-life of the product. These measures go against the profit-making motive of companies in this capitalist system. Green marketing and labels allow companies to evade their responsibilities in reducing GHG emissions and protecting the environment. There needs to be strict regulations and penalties to prevent companies from using greenwashing tactics and to ensure that they adhere to sustainable practices.

References

- Naderer, B., Schmuck, D. & Matthes, J. (2017). 2.3 Greenwashing: Disinformation through Green Advertising. In G. Siegert, M. Rimscha & S. Grubenmann (Ed.), Commercial Communication in the Digital Age: Information or Disinformation? (pp. 105-120). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110416794-007

- de Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & Soares, G. R. D. L. (2020, February 11). Concepts and forms of greenwashing: a systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

- Break Free From Plastic. (2022). Brand Audit 2021 | Brand Audit. Brand Audit. https://brandaudit.breakfreefromplastic.org/brand-audit-2021/

- Arfat. (2023). The problem of greenwashing in India: Policy review. GGI. https://www.theggi.org/post/the-problem-ofgreenwashinginindia#:~:text=1.1%20Prevalent%20issue%20of%20greenwashing%20in%20India&text=For%20instance%2C%20a%20study%20by,and%20accountability%20in%20the%20market

- Zhang, J., & Yang, J. (2022). Influence of Greenwashing Strategy on Pricing: A Game-Theoretical Model for Quality Heterogeneous Enterprises. Advances in Transdisciplinary Engineering. https://doi.org/10.3233/atde220300

- Cetin, C. B., Mukherjee, A., & Zaccour, G. (2023). Strategic Pricing and Investment in Environmental Quality by an Incumbent Facing a Greenwasher Entrant. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4454279

- Dechezleprêtre, A., D. Nachtigall and F. Venmans (2018), “The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1515, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/4819b016-en

Recent Comments