Restoring the River: Launch and Objectives

India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, eloquently expressed that Ganga represents the country’s rich and memorable past, continuously flowing into the present and towards the ocean of the future. The National Mission for Clean Ganga (Namami Gange) (NMCG) fully funded by the Union Government of India, launched in June 2014 with a budget of Rs. 20,000 crores, is a comprehensive programme aimed at reducing pollution, conserving, and rejuvenating the river. It includes short, medium, and long-term plans for sewage treatment plant upgrades, pollution reduction measures, research, and restoration efforts. It is one step towards ensuring the long-term viability of this revered river, which has enormous cultural, spiritual, and ecological significance in India.

Promises of the Restoration Project

The Namami Gange programme is carried out through eight strategic sectors.

1. Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs): STPs play an important role in reducing toxic effluent discharge from human settlements and industries. Wastewater treatment offers not only environmental and health benefits, but also economic advantages through its potential for reuse in various sectors. The by-products derived from the treatment process, such as nutrients and biogas, can be utilised in agriculture and energy generation, providing additional revenue streams. These revenues can help offset the operational and maintenance costs of water utilities, making wastewater treatment a financially viable option.

2. River-Front Development projects aim to create public spaces along the riverfront, allowing people to appreciate the river and its surroundings.

3. Industrial Effluent Monitoring: Inspections of Grossly Polluting Industries are conducted on a regular basis to ensure compliance with environmental standards and to prevent pollution from industries.

4. Ganga Gram: This sector works to improve sanitation and reduce open defecation by constructing toilets in over 1600 Gram Panchayats along the river.

5. River Surface Cleaning: This sector aims to address the issue of river pollution caused by solid waste and debris by focusing on priority locations for debris collection and cleaning.

6. Biodiversity Conservation: This sector focuses on restoring endangered biodiversity in the Ganga River, including aquatic and terrestrial species conservation.

7. Afforestation: Forestry interventions are carried out in order to increase forest productivity and restore riparian areas, thereby contributing to the conservation of the Ganga river ecosystem.

8. Public Awareness: This sector aims to raise awareness and promote responsible actions for the rejuvenation and conservation of the Ganga river through workshops, campaigns, media outreach, and community participation.

Evaluating the Efforts to Restore the Ganga River

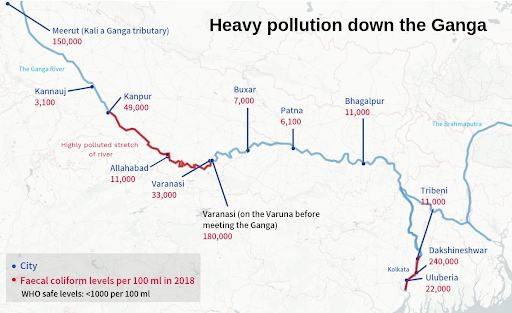

Despite significant efforts and numerous ongoing projects, the ambitious goal of restoring the Ganga river by 2020 was not entirely met. The current situation is a result of a number of issues, including underutilization of funds, delays in project implementation and the slow progress of sewage infrastructure projects.

One of the most significant challenges has been the slow progress of sewage infrastructure projects. Although 66 projects have been approved since May 2015, only six have been completed, with the majority still being pending. Out of all projects that received approvals in 2017, less than 50% show more than 50% progress even if we consider the delays caused due to covid, again, dishonouring deadlines. Moreover, 28 projects are still in the tendering stage, delaying their implementation even further. Institutional development has also been hampered, with nine new projects totaling Rs 773.9 crore planned but no funds allocated despite the release of Rs 21.12 crore. Similarly, funds allocated for other sectors’ improvements have not been fully utilised, resulting in idle funds.

Acknowledging the shortcomings on every front of NMCG, the deadline for achieving the aforementioned goals was extended till 2026. The second phase of the program focuses on efficient utilisation of funds, hastening the tendering process and regular assessments to form a clearer idea on the progress and making improvements as we go by. This requires coordinated efforts from numerous stakeholders, including local communities, non profit organisations and government establishments.

The government has implemented 409 projects in the second phase at an estimated cost of Rs. 32,912.40 Crore. These initiatives aim to build sewage infrastructure because the main source of river pollution is untreated domestic and industrial wastewater. Out of the total projects started, 232 have been completed and are presently operational, with the remaining projects being in various stages of development. The creation of sewage infrastructure makes up the majority of the projects, with 177 sewerage projects costing Rs. 26,673.06 Crore. This includes installing a 5,213.49 KM sewerage network and renovating and expanding the 5,269.87 MLD capacity of sewage treatment plants (STPs).

A Paradigm Shift: Takeaways from Nagpur and Thames

On similar lines as Ganga, but worse, river Thames in England suffered from direct sewage waste disposal, heavy construction on its floodplains and loss of aquatic ecosystem in the victorian era, all of which combined, gave the river a foul stench, infamously known as The Great Stink. However, the success story of the Thames cleaning project promises hope that if a biologically dead river can be made chart-toppingly clean, so can Ganges. But not without a paradigm shift. When it was ‘show time’ for authorities during Ardh Kumbh Mela, Tehri Dam (built on Ganga in Uttarakhand) released extra water, along with temporary shutting of heavily polluted tanneries in Kanpur (Kaur & Sengupta, 2019). The point remains, band-aid won’t treat a gaping wound.

Though Thames’ example looks far-fetched, its essence is captured by the city of Nagpur that saves 190mn litres of freshwater every day by treating and then reusing its sewage water in power plants. This translates into clean main rivers of the city i.e. the Nag, Pavi and Pohara Rivers, no requirement of searching for alternative water sources for next 15 years, no need for environmentally destructive dams, royalty for Nagpur Municipal Corporation and assured business for the Nagpur Waste Water Pvt. Ltd for next 25 years. It is noteworthy that the building India’s largest water treatment for reuse project was completed in 15 months only against the estimated time of 24 months (Tare, 2021). Then what hurdles does NMCG face? Note; underutilization of funds, delays in project implementation and the slow progress of sewage infrastructure projects are plain consequences. A shortage of political will implicitly remains the root cause.

Ecological Flow of Ganga and Ignored Reports

The Environmental Flow (simply E-Flow) is the flow necessary to maintain ecological integrity of rivers, their associated ecosystems and the goods and services provided by them. The following table summarises the suggested E-flow levels by various reports and committees till date. Other than this, it is a fact that the government of India has maintained an E-flow level of 20-30% in Ganga that has come under criticism by scientists and IIT scholars, saying that there should be enough water in the river for it to have life. Ganga is dry at many spots.

| Year | Recommended By | Recommended E-Flow Level | Special Remarks |

| 2006 | International Water Management Institute | 67% | |

| 2011 | Allahabad High Court | 50% | |

| 2012 | World Wildlife Fund | 45-47% (Kachla Ghat plains and Bithoor) | |

| 2012 | World Wildlife Fund | 72% (Mountains of Kaudiyala) | |

| 2012 | Wildlife Institute of Institute | 20-30% | Became the basis of 2017 report |

| 2013 | Inter-Ministerial Recommendation | 20-30% | |

| 2014 | 7 IITs together (approved by by Water Ministry and NMCG) | 47% | Not used by government in 2017 saying that IIT unnecessarily increased depth for assessment from 0.5, 0.8, 3.41 to 0.5, 0.8, 1.8 in metres in dry, normal and rainy seasons respectively |

| 2017 | 3 member committee headed by Uma Bharthi | 20-30% | No fresh assessment made, when asked about no data in report, government stated that it is not included in policy documents |

(When It Comes to Ganga’s Health, the Centre Has Ignored Several Key Reports, n.d.)

A river needs to have adequate flow, to support life and secondly to support its natural self-cleansing mechanism. Government is aware of this because they talk about Aviral Ganga in NMCG, yet act obliviously. The 3 member committee headed by Uma Bharathi did not cite a reason for excluding data and facts from their policy report. Additionally, a report by 7 IITs was disregarded by the Central Water Commission owing to differences in its assessment methodologies, without rational justification.

The fact that during Ardh Kumbh 7000 cusecs of extra water was released till its conclusion and 8000 cusecs on the day of Royal Snan (mentioned earlier), highlights how government succumbs to what environmentalists like Guru Das Agarwal who sacrificed their life after fasting for stopping destructive damming and polluting of Bhagirathi (Ganga) repeatedly say (Kaur & Sengupta, 2019; Kaur, 2018). If E-flow really needs to be 20-30% then why release extra water to show off cleanliness in a mega event?

Conclusion

Subject to improvements, the potential solution to combat inefficiency and ineffectiveness issues of Namani Gange programme that this article suggests, is releasing and using the allocated funds for sub-projects on time, meeting deadlines and learning from Nagpur’s municipal corporation to reuse treated water in power plants. This means reduced pressure on dams and reduced electricity problems during summers as power cuts during summers across many places in India happen because of no availability of water to power houses. Additionally, increase the E-flow level of Ganga with proper reassessment and do not release untreated waste into the source of life, not just on paper but in real terms.

References

- Ahmad, O. (2021, April 29). A clean Kumbh in a dirty Ganga. The Third Pole.

- From ‘biologically dead’ to chart-toppingly clean: how the Thames made an extraordinary recovery over 60 years. (n.d.).

- Tare, K. D. (2021, March 25). Good news: How a sewage treatment plant in Nagpur saves 190 million litres of fresh water per day. India Today.

- Kaur, B., & Sengupta, S. (2019, January 25). Kumbh is fine but why not clean the Ganga all the time? Down To Earth. Retrieved April 16, 2023

- Kaur, B. (2018, October 13). Ganga’s minimum flow notification too vague to be implemented: Scientists. Down To Earth. Retrieved April 17, 2023

- Mishra, D. (2021, February 12). When It Comes to Ganga’s Health, the Centre Has Ignored Several Key Reports. The Wire. Retrieved April 18, 2023

- Dhairya Maheshwari, & Maheshwari, D. (2018, October 21). Namami Gange: Why it is a failure. National Herald.

- Mathur, A. (2020). Namami Gange Scheme – A Success or mere propaganda?

- Kohli, K. (2018). Gadkari’s clean Ganga promise by 2020 far-fetched? A fact-check on progress of vital schemes. ThePrint.

- National Mission for Clean Ganga(NMCG),Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation, Government of India. (n.d.). नमामि गंगे.

- SCHEMES FOR CLEANING OF RIVERS. (n.d.).

- Sharma, P. (2023, January 28). ’By 2025, drains will stop flowing into Ganga’ : DG, National Mission for Clean Ganga. The Week.

- Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India. (2021). NMCG Annual Report 2020-21. National Mission for Cleaning Ganga. Retrieved April 10, 2023, from https://nmcg.nic.in/

Rishita Jain

[email protected]

B.A. (P)- Economics & Human Resource Management, 2nd Year

Indraprastha College for Women, D.U.

Great Read!